Starlin Castro, right, was congratulated in the dugout after leading off the sixth inning with a home run.

Yankees Manager Joe Girardi is a man who seeks out certainty. He does not like hypotheticals, waving away what-ifs as though they were a child with too many questions.

But on Wednesday, an unexpected possibility loomed, one so tantalizing that even Girardi could not help but consider it: a chance to catch the Boston Red Sox at the top of the American League East.

After seemingly cementing the division title last weekend, the Red Sox lost consecutive games at home to the Toronto Blue Jays, allowing the Yankees to creep within three games with just five to play.

The Yankees did their best to further close the gap, defeating the Tampa Bay Rays, 6-1, on Wednesday night at Yankee Stadium. But the Red Sox steadied themselves, rallying from a three-run deficit to beat back the Blue Jays, 10-7, to narrow their magic number for clinching the division to any combination of two wins or Yankees losses.

Even if the Yankees are unable to chase down the Red Sox, there will at least be a consolation that they pressured their rivals to the end. Since they last played the Red Sox, on Labor Day weekend, the Yankees have won 16 of 22 games but have only narrowed their deficit behind Boston by a half-game.

“I probably don’t even think about it sometimes,” first baseman Greg Bird said of the division standings. “I was looking today, though. Someone when I was on deck was saying the Sox are losing 3- or 4-1, and then I looked up and it was 9-4. So, I missed a lot there.”

Continue reading the main story

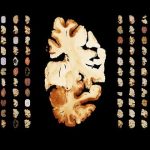

number of scientists argue that because the human brain develops rapidly at young ages, especially between 10 and 12, children should not play tackle football until their teenage years.

number of scientists argue that because the human brain develops rapidly at young ages, especially between 10 and 12, children should not play tackle football until their teenage years.