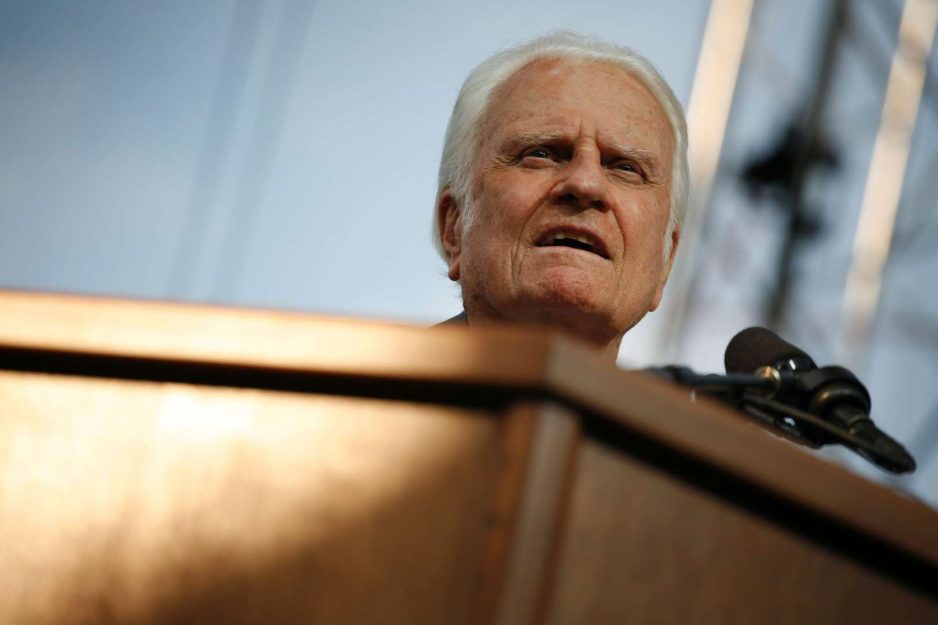

Billy Graham and Ruth Bell met at Wheaton College in the fall of 1940. A vivacious and feisty beauty who had grown up in China as the daughter of Presbyterian medical missionaries, Ruth was the prize catch of her class. After a first date, to a performance of Handel’s “Messiah,” Billy wrote home to announce that he had met the girl he planned to marry. Ruth described Billy as “a man that knew God in a very unusual way.” Graham died Wednesday in his home in Montreat, N.C., at the age of 99.

The courtship between Billy and Ruth, though hardly rocky by conventional measures, faced a formidable obstacle. Both felt called to serve God, but Ruth had long dreamed of evangelizing Tibet, whereas Billy had thought of preaching in fields rather more “white unto harvest.” He respected Ruth’s noble aspiration, but because he felt no Himalayan call himself, he convinced her that not to choose his course would be to thwart God’s obvious will.

After Ruth acknowledged that she wanted to be his wife, he pointed out that the Bible says the husband is head of the wife and declared, “Then I’ll do the leading and you do the following.” Though only the blindest of observers would conclude that Ruth Bell ever surrendered her will or her independence, she soon began to learn what following Billy Graham would mean.

After their marriage in August 1943, Ruth caught a chill while returning from their honeymoon. Instead of calling to cancel a routine preaching engagement in Ohio and staying at the bedside of his new bride, Billy checked her into a hospital and kept the appointment, sending her a telegram and a box of candy for consolation. She felt hurt, but soon learned that nothing came before preaching on her husband’s list of priorities.

In 1945, Graham became a full-time evangelist, a job that had him traveling throughout the United States and Europe. Perhaps sensing the start of a lifelong pattern, and pregnant with their first child, Ruth moved in with her parents in Montreat, N.C., a Presbyterian retirement community. The Bells provided her with companionship to ease the loneliness she felt during her husband’s long absences and were there to share important moments — when their first child, Virginia (always called “Gigi”), was born in 1945, Billy was away on a preaching trip.

As Graham’s crusades took him throughout the world, little was left for Ruth and the children — Gigi, Anne, then Ruth (long called Bunny), Franklin and Ned. Once, when Ruth brought Anne to a crusade and let her surprise her father while he was talking on the telephone, he stared at the toddler with a blank look, not recognizing his own daughter. In a turnabout a few years later, young Franklin greeted his father’s homecoming from a crusade with a puzzled, “Who he?”

To keep him in their hearts and minds, Ruth read Billy’s letters aloud and guided the children as they prayed for him and his work. On Sunday afternoons, she gathered them together to listen to his voice on the “Hour of Decision” broadcast. Afterward, he usually called to talk with each of them.

If the children commented on their father’s absence, they were told he had “gone somewhere to tell the people about Jesus.” Gigi remembered that “Mother never said, ‘Daddy’s going away for a month.’ Instead, she would say, ‘Daddy will be home in a month. We’ll do such and such before he comes back.’ ” She also noted that, particularly when she was younger, “I thought everyone’s daddy was gone. And my granddaddy was such a father figure for us, that it never hit me that it was all that unusual.”

Whether it was perceived as unusual or not, the children did notice their father’s absence. Once, Ruth saw one of the girls sitting on the lawn, staring wistfully at an airplane in the distance and calling out, “Bye, Daddy! Bye, Daddy!” A plane meant Daddy was going somewhere.

Acquaintances from the early years remember that the Graham youngsters were less than models of decorum in their behavior at church and other public gatherings, but Ruth did her best to exercise a rather stern and consistent discipline at home. She claimed to have obtained some of her most effective child-rearing techniques from a dog-training manual whose directives included keeping commands simple and at a minimum, seeing to it that they were obeyed, rewarding obedience with praise and being consistent.

Gigi recalled, “She was strict. I got spanked nearly every day. Franklin, too. Anne didn’t seem to need it. But Mother had a great sense of humor, and we had a lot of fun. I have no memories of a screaming mother.”

When Billy was home, which was less than half the time, much of Ruth’s disciplinary regimen went out the window. “Mother would have us in a routine,” Gigi recalled. “She monitored our TV watching, made us do our homework, and put us to bed at a set time. Then, when Daddy was home, he’d say, ‘Oh, let them stay up and watch this TV show with me,’ or he’d give us extra spending money for candy and gum. Mother always handled it with grace. She never said, ‘Well, here comes Bill. Everything I’m trying to do is going to be all messed up.’ She just said, ‘Whatever your daddy says is fine with me.’ ”

Gigi offered a possible explanation of her father’s more relaxed approach. “Once, he disciplined me for something I did. I don’t even remember what it was about, but we had some disagreement in the kitchen. I ran up the stairs, and when I thought I was out of range, I stomped my feet. Then I ran into my room and locked my door. He came up the stairs, two at a time it sounded like, and he was angry. When I finally opened the door, he pulled me across the room, sat me on the bed, and gave me a real tongue-lashing. I said, ‘Some dad you are! You go away and leave us all the time!’ Immediately, his eyes filled with tears. It just broke my heart. That whole scene was always a part of my memory bank after that. I realized he was making a sacrifice, too. But it does seem like he didn’t discipline us much after that.”

Over time, Ruth also became more flexible, reducing the number of her demands on the children to those she thought were essential. But when they reached an appropriate age, she and Billy sent all of them off to boarding school. Bunny acknowledged that part of their motivation might have been to provide their children with a better education than was available locally, but thought that was a minor factor. “Daddy was burdened, Mother was overwhelmed. It was easier to send us away.”

Like her sisters, Bunny remembers being groomed for the life of wife, homemaker and mother. “There was never an idea of a career for us,” she said. “I wanted to go to nursing school — Wheaton had a five-year program — but Daddy said no. No reason, no explanation, just ‘No.’ It wasn’t confrontational and he wasn’t angry, but when he decided, that was the end of it.” She added, “He has forgotten that. Mother has not.”

Franklin was always a handful. As an adolescent, he smoke, drank and drove fast, practices echoed in his adult image — he still rides a Harley, often preaches in a motorcycle jacket, and his first book was titled, “Rebel With a Cause.”

Ned, the youngest sibling, manifested his rebellion by turning to more than a casual use of drugs, including cocaine. “While I was embroiled in all that,” he recalled, “my parents were just very patient. They expressed concern and displeasure over the behavior, but never once did they make me feel they rejected me as a person. Their love for me was always unconditional. Their home was always open, no matter what condition I was in. They gave themselves to me, and I never felt their love was conditioned on meeting some requirement. Eventually, their grace and love were just irresistible.”

As adults, publicly and to a large extent privately, the Graham offspring have seldom said anything more negative about their family life than, “We weren’t perfect.” In recent years, daughter Ruth — now no longer known as Bunny — has been more outspoken about what she regards as the disadvantages of growing up in a famous family.

“My father’s relation with the family has been awkward,” she said in a 2005 interview, “because he has two families: BGEA [the Billy Graham Evangelistic Association] and us. I always resented that. We were footnotes in books — literally. Well, we’re not footnotes. We are real, living, breathing people.”

She said there was no question her father loved them, but his ministry was all-consuming. “We have coped,” she said. “We have not rejected them or Christ. We’re all involved in some form of ministry. We have done well at living up to people’s expectations, but it is a burden. We were not a perfect family and I’m tired of people saying it. I don’t want to be indiscreet, but God inhabits honesty, and I’m not good at image-management.”

Three of the five Graham children have divorced. Ruth was the first. When she discovered that her husband had been engaged in a long-running affair, she was devastated. “At first I resorted to my familiar pattern of denial — covering over my hurt with spiritual platitudes. I prayed. I fasted. I forgave. I claimed Bible promises. I did all I’d been taught to do. I also hid my problems from everyone, humiliated that others — especially my family — would find out.”

Her family did find out, of course, and Graham strongly urged her not to divorce, telling her it would hurt millions of evangelical Christians who looked to his ministry and their family for inspiration.

After one crucial conversation, Ruth recalled, “I saw how important the ministry was to him — and how little the family was. Things had to look right, and divorce didn’t fit.” Ruth acknowledged, however, that once they realized the marriage was over, they “were always very loving.” “Inside, there was that core of love and grace and gentleness. I’m not sure Daddy could understand the hurt I felt, but he could understand broken trust. That’s where we could communicate. He has been betrayed, hurt, and gone ahead.”

Ruth soon realized that countless Christian families have been torn apart or severely injured by similar stresses and that, contrary to her and her father’s fears, her divorce was “barely a blip on the radar screen.” She has used her experiences to communicate the truth that even the most famous Christians are not exempt from the problems that trouble most people. “We all,” she said, “still have to work through the mess and muck of life. You can’t just slap a Bible verse over a wound and expect it to heal.”

In several books and in conferences titled, “Ruth Graham & Friends,” she joins with other women to share stories of coping with the pains of such troubles as infidelity, spousal abuse, divorce, illness and addiction.

She writes of the difficulties of being part of an often idealized but still quite human family and assures her audiences, “God doesn’t love Billy Graham or his family any more than he loves you.”

William Martin is the Harry & Hazel Chavanne professor emeritus of religion and public policy at Rice University. He is the author of “A Prophet with Honor: The Billy Graham Story,” (William Morrow, 1991). An updated edition is being published by Zondervan.

SOURCE

City crusade in 2005 was sponsored by 1,400 regional churches from 82 denominations. In recent years, he was plagued by various ailments, including cancer and pneumonia.

City crusade in 2005 was sponsored by 1,400 regional churches from 82 denominations. In recent years, he was plagued by various ailments, including cancer and pneumonia.